Adult Shearwaters mistake floating plastic for prey, unwittingly feed it to their chicks.

By Stephen Wright for RFA

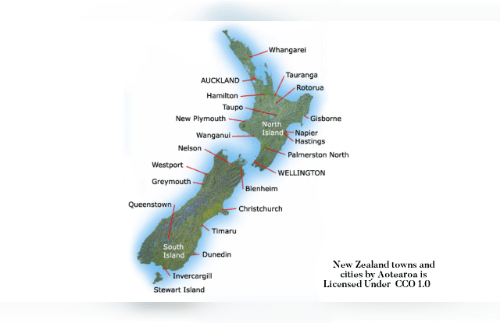

Promoted as “Just Paradise,” Lord Howe Island hundreds of kilometers east of Australia is a unique environment home to plants and fauna found nowhere else in the world.

This pristine and remote remnant of an ancient volcano is also the nesting site of a far-ranging species of seabird that has become a signature casualty of the vast amounts of plastic waste entering the oceans.

A recent study by Australian researchers has provided alarming new evidence of the plastics burden on wildlife. It points to profound changes in Sable Shearwater chicks unwittingly fed plastic by their parents – from signs of failing organs to brain damage that could impair the ability to mate.

Every year, dead birds wash up on the beaches of Lord Howe Island, sometimes in their hundreds, with what researchers say are severe symptoms of swallowing large amounts of plastic – emaciation, poorly developed feathers and deformities.

For their study, the researchers turned their attention to Shearwater chicks that appeared outwardly healthy to understand what deeper changes could be occurring.

“These apparently healthy chicks are already compromised,” said Jack Rivers-Auty, an immune system expert at University of Tasmania’s medical school. “We’re now seeing that reflected in poorer survival outcomes and weight trajectories over time,” he told Radio Free Asia.

“By studying birds that seem outwardly well, we can more clearly assess the hidden impact of plastic on their long-term survival and physiology,” he said.

Lord Howe is close to the east Australian current that carries warm Coral Sea waters south. Relatively still ocean eddies that form off the current are places where floating debris including plastics can accumulate into rafts of debris. Shearwaters likely mistake the objects for prey, especially squid, a main part of their diet – ingesting it themselves and also feeding it to their offspring.

The birds’ migration takes them over most of the Pacific Ocean, which Jennifer Provencher, a conservation biologist not involved in the study, said means they “have an incredible exposure to plastics for their entire lifecycle.”

The stress of ingesting lots of plastic – which the species, unlike gulls, can’t regurgitate unassisted – likely also manifests itself in hormonal changes that impair the robustness of eggs and chicks, Provencher told RFA.

“It’s a combination of this bird’s inability to barf things back up and the fact that they live and migrate throughout the entire Pacific Ocean,” she said.

The study uses “very cool” techniques, Provencher said, but more research is needed to gauge the relevance to seabirds in general, which number in the hundreds of species.

“It’s hard to generalize,” she said. “More understanding is needed of how applicable this work is beyond this species and this place.”

Convenient and cheap, plastics are produced in ever growing volumes and found in every nook and cranny of daily life – from the flimsy stools at street food stalls in Southeast Asia to the componentry of sophisticated smartphones and the hundreds of billions of water bottles and plastic bags discarded worldwide every year after just seconds of use.

Mostly unrecycled, plastic waste has a lifespan of centuries and is exacting an increasing toll on the environment including in the oceans where it injures and kills marine and bird life.

Oil producers including Russia and Saudi Arabia slowed negotiations on an international treaty to control plastic waste to a crawl.

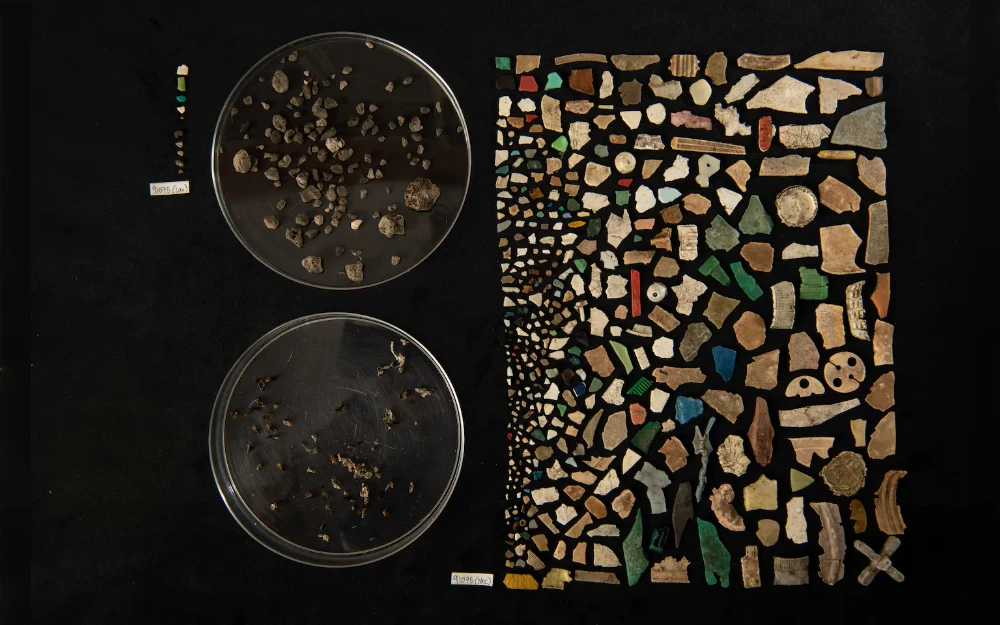

In April and May of 2023, the Australian researchers captured healthy looking Shearwater chicks on Lord Howe Island and flushed their stomachs with water – a technique known as gastric lavage – to induce regurgitation.

If they vomited less than five pieces of plastic or 0.5 grams in total, they were categorized as being less plastic exposed and vice versa.

One chick vomited up 403 pieces of plastic.

Using a relatively novel technique, the blood of the chicks was analyzed for an array of proteins and other signatures, which provided telltale signs of greater health effects for chicks that had larger quantities of plastic in their stomachs.

Cell contents that should not be found in the blood were frequently detected, which the researchers said was indicative of cell breakdown.

Proteins secreted by organs were less abundant, indicating that the stomach, liver and kidneys were not functioning normally, according to the study.

The signatures included evidence of neurodegeneration in chicks less than three months old that has the potential to affect the birds’ “song-control system” – crucial for identifying the opposite sex and courtship.

The researchers’ theory is that the swallowed plastic is shedding very small fragments known as microplastics that are transported into the organs.

Leaching of chemicals from the plastic is another possibility.

“It’s a bit like smoking: from the outside, a smoker might look fine, but internally, significant health issues are often developing,” said Auty.

“We’ve documented plastic items originating from all over the Pacific, including debris with non-English writing, which shows how far these plastics are traveling,” Auty said.

“It’s not just local pollution. It’s a global issue washing up and circulating in the region.”

Edited by Mike Firn and Taejun Kang.

“Copyright © 1998-2023, RFA.

Used with the permission of Radio Free Asia,

2025 M St. NW, Suite 300, Washington, D.C. 20036.

https://www.rfa.org.”